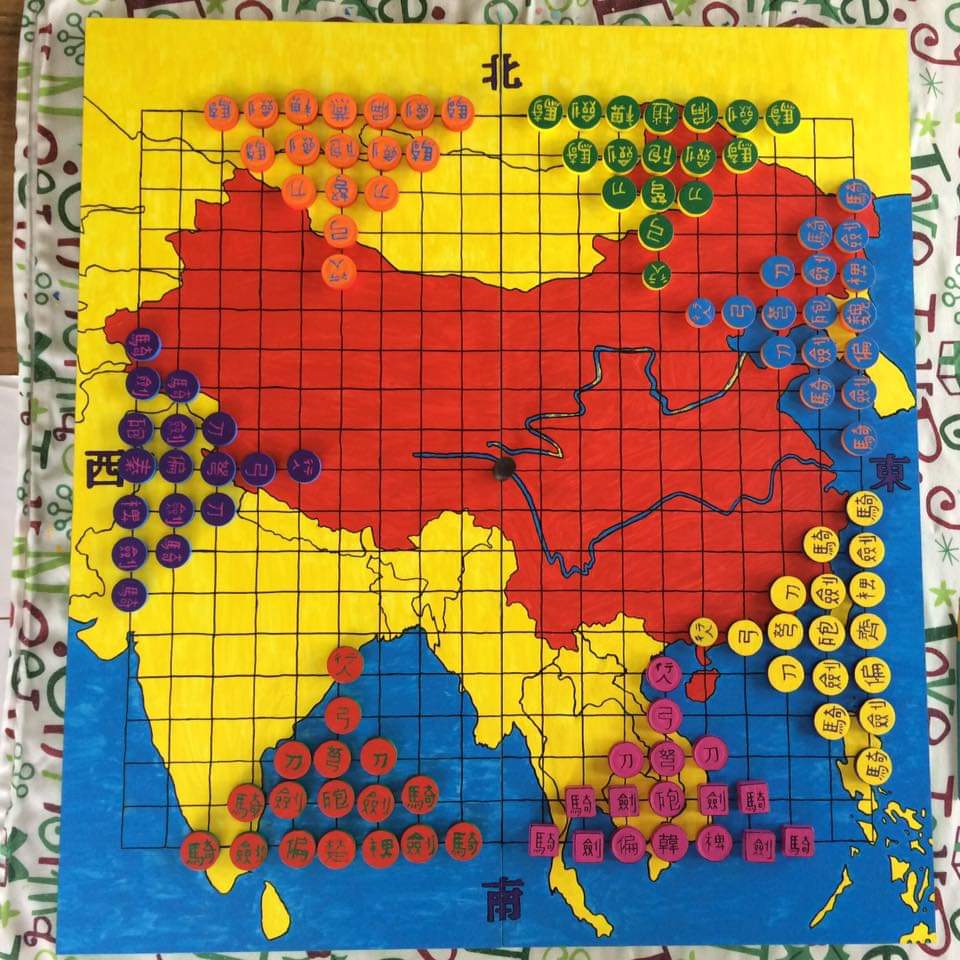

Some claim that chess and math go hand in hand. Indeed, certain mathematical issues can be applied to chess: the well-known wheat grain, a knight moving over the whole board without coming on the same square more than once, or place eight queens in such a way that they do not attack each other. Others would say art, although this is more complicated because two artists are working on one piece of art at the same time, or even sports, although that doesn’t necessarily exclude the other approaches. The Freudian sees the Oedipus complex, where checkmating the enemy king represents murdering the father. Everyone interprets things in their own way. I am no different; whenever I’m learning a new foreign language, the first thing I do is have a look at the names of the chess pieces and of the game itself. When are the footmen being called soldiers and when farmers? When is a rook a chariot and when a boat?

In Europe we consider the queen to be the king’s consort. The queen in her modern shape was introduced at the beginning of the 15th century, when the game of chess took its current form, and Joan of Arc lived as well. A connection seems obvious, but in reality there already was a trend going on of speeding up the game. The bishop was allowed to move along the whole diagonal instead of one or two squares and the pawn could even make two steps forward on the first move.

An important source language for naming the pieces is Arabic. For queen the Arabic term for minister (wazīr) is used, as well as in various other languages in the Middle East. Spanish and Italian have borrowed their words for bishop alfil and alfiere respectively, from the Arabic word al-fīl, literally meaning “the elephant.” Why do the Spaniards borrow their word for bishop from another language, while their Portuguese neighbour use the European concept of bishop, like in English? After all, it was the Spanish bishop Ruy López de Segura who had experimented with 3. Bb5 in the sixteenth century.

If chess indeed reflects society, different names must say something about the culture in which the game is played. This is not a fixed rule – language itself is full of exceptions – but there are definitely patterns that can be pointed out. More than enough material for a dissertation, that’s for sure.

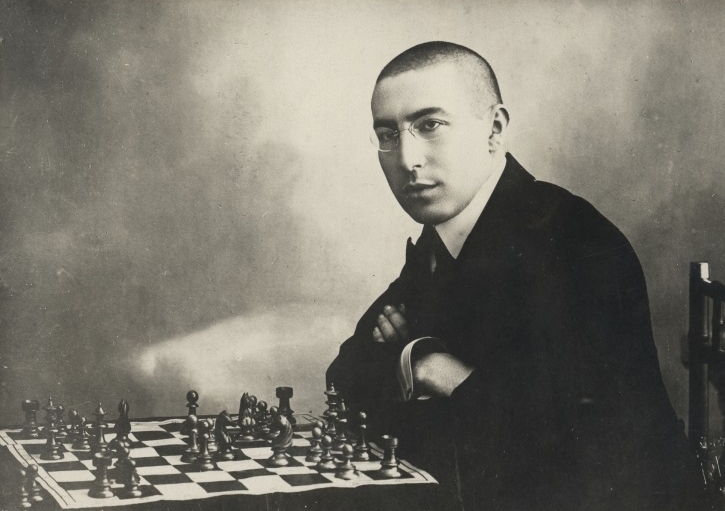

FM Zyon Kollen studies Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Leiden. He won the Amsterdam Science Park Tournament in 2018 and he hunts for a norm at the Chess Festival. The 24-year old Kollen speaks six languages fluently, e.g. Finnish, Swedish and Portuguese. He is also a chess trainer, chess set collector and builder, and he writes reviews on chess books. His columns will be published every day on the website around 12 o’clock.